[Revised from an article originally published in Laura Grey’s Little Hopping Bird blog.]

You’d be shocked if a coworker said she could gauge the intelligence of a member of your company by the color of her skin, wouldn’t you? If your child’s teacher said Muslim kids aren’t trustworthy, you’d notify the principal at once. If your favorite cafe’s owner said he disliked gay people, his blatant bigotry would ensure that you’d never eat his risotto again. You’re careful not to stereotype people in wheelchairs or wheatgrass juice drinkers, lesbians or limo drivers, Estonians or the elderly. You see how ridiculous it is to ascribe personality traits to whole groups, or make generalizations about ability or behavior based on so little information. You expect your friends, family and coworkers to show the same respect to others that you do.

So, why are so many otherwise sensitive, multiculturally aware folks so willing to put down the little guy? Why does society hold such contempt for short men? Why are smaller-than-average fellows passed over for jobs, relationships and pay raises at higher rates than other men? And why are jokes and snide asides about short men being less confident, virile or capable so pervasive?

Easy laughs at the expense of men who are mere inches shorter than average are commonly accepted in daily conversation, in ads, in TV shows and films, at work. Even the rare man who shares my own height of just five feet two inches is only 10% smaller than a man of average stature in the U.S., and most men who are publicly berated for being short come within 5% of average height. Why do we ascribe so much social importance and status to such a small variance in size?

My own height is below the 25th percentile for American women, so I’ve always been aware of society’s preference for taller people. But as a petite female, I sometimes benefit from stereotypes about small women. Short women are often assumed to be cuter, nicer or more approachable before people even get to know us. Our stature is less threatening, so strangers often assume our personalities will follow suit. Because people expect us to be friendlier, meeker and weaker than average, they might let down their guard more easily with us and be more willing to help us. However, they also condescend more, sometimes assume we’re less capable or even less intelligent, and not infrequently they offer assistance we haven’t asked for and don’t want, sometimes insistently, as if being smaller than they are means we can’t be trusted to gauge our own strength and ability appropriately.

In study after study, the majority of men say they much prefer dating women who are smaller than they are. Shorter-than-average women make men feel bigger and stronger in comparison with taller women. Tall women definitely find it harder to find men who are comfortable dating them, and they say overwhelmingly that they prefer to date men even taller than they. They then hear fewer comments about their height and get less attention for sticking out in a crowd. But tall women also have a lot of positive characteristics ascribed to them. They’re assumed to be more capable and powerful in social, academic and business settings, so they earn more money as a group than their smaller sisters. There are various advantages to being taller than average, of medium height or even shorter than average height for women, and men of taller-than-average height gain noticeable benefits in social, financial, academic, business and governmental realms. But short men? They’re at a social disadvantage across the board.

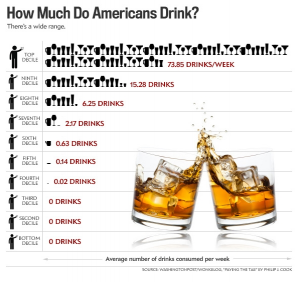

Surveys of attitudes reveal that people both perceive and treat people of shorter stature as inferior. This is particularly notable in the business sphere. International university studies have shown that short people, male and female, are paid less than taller people, with disparities similar in magnitude to those ascribed to race and gender gaps. Tall people have significant advantages when it comes to hiring, pay, promotions and prominence within their companies. A 2005 survey of the heights of Fortune 500 companies’ CEOs revealed that they were on average six feet tall, approximately three inches taller than the average U.S. man. Fully 30% of these CEOs were six feet two inches tall or more. Ninety percent of CEOs are of above average height.

In the U.S., taller candidates have the advantage in electoral politics, though heightism isn’t a problem in Russia, where President Vladimir Putin is just over five feet seven and former President Dmitry Medvedev is just over five feet five inches tall. France’s former President Nicolas Sarkozy is just over five feet six. He is married to the former model Carla Bruni, who is five feet nine inches tall, and throughout his tenure this fact was constantly remarked upon throughout the world. Endless jokes were made about his power being enough of an aphrodisiac to make up for his lack of height, which many assume would otherwise make him appear weak and sexually less desirable. As if a man’s attractiveness, sexual skill or ability to be a good husband had anything to do with his height!

Shockingly, heightism has been cited as one of the underlying causes of the Rwandan genocide, in which approximately one million people were killed. One of the reasons that political power was conferred on minority Tutsis by the exiting Belgians was reportedly because Tutsis were taller and were therefore seen by the Belgians as superior and more suited to governance than Hutus. That’s a horrifying price to pay for baseless prejudice, isn’t it?

Why do a few inches of height matter so much that over 90% of women say they wouldn’t want to date someone shorter than they are? Why do men and women find being of short stature so risible? Film and TV directors often elicit laughs by having a short man make an entrance in a scene when a man of power, action or attractiveness is expected, playing off the audience’s expectation that a charismatic individual must be tall. Think for a moment about how often people laugh at the mere idea that a short man could be considered worthy of their admiration, just as people used to laugh at the idea of showing respect to women, black people or gays and lesbians.

Much loved actor Peter Dinklage, who plays Tyrion Lannister in HBO’s Game of Thrones and was so moving in the film The Station Agent, has made a career of playing bright, serious men with dwarfism in a world in which people make constant assumptions about their ability, their personalities or their manhood based on nothing more than height. The brilliant economist Robert Reich met Bill Clinton while they were Rhodes Scholars; he went on to be Clinton’s labor secretary and is now a professor at UC Berkeley. He is a particularly witty and pleasant fellow, and is quite willing to make jokes about his four-foot-ten-inch stature. He has to be a good sport about this; it is cited as a relevant fact about him far too frequently. Reich is wise to let this roll off his back; when short men show fatigue or frustration at the frequent comments and stares, the public that so enjoys razzing them about this inane fact is all too quick to turn nasty and attribute a panoply of bad characteristics to them based on, yes, their lack of height.

We’ve all heard that short men are supposed to be prone to the Napoleon Complex, or Little Man Syndrome, an alleged type of inferiority complex said to affect men of short stature who attempt to overcompensate for their height in other aspects of their lives. Yet this supposed syndrome or complex does not appear in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Ironically, Napoleon Bonaparte was, at five feet six, taller than the average European man of his time. Yet how many images have you seen of Napoleon depicted as unnaturally short, and how many times has that trope been used for comic effect? He and countless men of less-than-average height have been depicted as angry, pompous and much shorter than they are, and the negative characteristics ascribed to them are often assumed to be related to a burning desire to overcome supposed embarrassment and self-hatred brought on by their height. Interestingly, research by Britain’s University of Central Lancashire shows that the supposed Napoleon Complex (described by them in terms of the theory that shorter men are more aggressive and try to dominate those who are taller than they are) was not in evidence in their experiments. In their studies, taller men were more likely to lose their tempers and be aggressive than shorter men. The Wessex Growth Study, a community-based longitudinal study conducted in the UK, monitored the psychological development of children from school entry to adulthood which found that “no significant differences in personality functioning or aspects of daily living were found which could be attributable to height”; this functioning included generalizations associated with the Napoleon Complex, such as risk-taking behaviors.

Think of how often this cliché appears in television, film and especially advertising. When people need visual shorthand to express negative characteristics, isn’t it remarkable how often they resort to using height as a signifier for social, sexual or business failure? The primary villain in the popular animated movie Shrek is Lord Farquaad, whose most notable physical characteristic is his extreme shortness. He is repeatedly made the butt of jokes about his stature, even in his presence, despite his power and authority. His every entrance is made more ridiculous by his attempts to conceal his lack of height. The idea that his dastardly and grandiose gestures are all efforts to compensate for shortness (or his supposed lack of virility) is not only alluded to tacitly but is explicitly mentioned numerous times. His small stature is, if you will, visual shorthand meant to allow the audience to detest and dehumanize him so that he can be made more hateful and ridiculous in our eyes.

Michael J. Fox has been an extremely popular actor and public figure for over 35 years. He is talented, likeable, attractive and witty, and his articulate and impassioned advocacy for stem cell research brings a huge amount of attention and funding to his cause. He suffers from Parkinson’s Disease, which often causes embarrassing physical tremors and even difficulty speaking, but he has been willing to brave the snide remarks and derision of people like Rush Limbaugh in order to help his others, no matter how difficult or exhausting public speaking are for him, and no matter how much travel and public scrutiny and exhaustion aggravate his symptoms. Yet, despite his remarkable efforts, which have allowed his foundation to fund over $450 million worth of research to help people with Parkinson’s to live better lives, public figures and private ones continue to make jokes about his height and caustically remark on his shortness, as if his size should in any way impact our ability to take him seriously.

Tom Cruise’s having had several wives taller than he is has gotten nearly as much press as his dismaying affiliation with Scientology, and has garnered much more press than stories of his actual acting talent or business acumen. His over-the-top demeanor and outspoken behavior certainly merit attention and even, at times, derision, but why is his height alluded to alongside descriptions of his behavior, as if the two were related? He is one of the most popular, lauded, influential, powerful and wealthy men of all time, yet there is usually a derisive smirk on the faces of commentators and poison in their prose when they refer to him. How many times have you heard journalists laugh because a shorty like Tom Cruise thinks himself worthy of the amazonian goddesses at his side? And how minuscule, how lilliputian, is this allegedly tiny and unworthy human being who thinks he’s man enough to stand next to Katie Holmes (who is five feet eight) or Nicole Kidman (who is five feet ten)? At five feet seven, he’s two inches shorter than the average U.S. male. Two inches. The width of a small lemon. But because he dares to fall in love with women who are taller than he, he is castigated and verbally emasculated by media outlets on a nearly daily basis. How ridiculous is that?

For the fun of it, consider the following list of shorter-than-average famous men. Consider their accomplishments, personalities, their talents, their influences on culture. Think about whether they fit general stereotypes of short men. Then consider whether you have unwittingly bought in to these stereotypes, or carelessly perpetuated any of them. It’s so common, and so easy to do. But it’s not fair. It’s time to stand up for the little guy.

Five feet tall: David Ben-Gurion • Andrew Carnegie • Danny DeVito • Fiorello LaGuardia

Five feet two: Buckminster Fuller • Paul Simon

Five feet three: Mohandas Gandhi • Martin Scorsese

Five feet four: Ludwig van Beethoven • Mel Brooks • Elton John • Pablo Picasso • Rod Serling • Auguste Rodin

Five feet five: Harry Houdini • J.R.R. Tolkien • Lou Reed • Armand Hammer • Gus Grissom • Sammy Davis Jr.

Five feet six: Alfred Hitchcock • Bob Dylan • Peter Falk • William Faulkner • Elijah Wood • Dustin Hoffman • Spud Webb • T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia)

Five feet seven: Martin Luther King, Jr. • Stephen Spielberg • Robin Williams • Mario Andretti • Bono • Doug Flutie • F. Scott Fitzgerald • David Eckstein • James Cagney • Salvador Dali • Al Pacino