[Revised from an article originally published in Laura Grey’s Little Hopping Bird blog.]

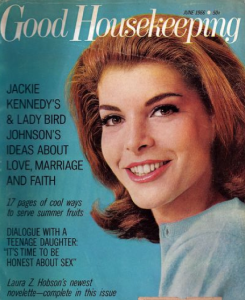

I recently purchased a great selection of vintage magazines dated from 1960 to 1971 and I’ve been enjoying stepping into the past each time I sit down to read them. My latest vintage magazine adventure has been with the June 1966 issue of McCall’s, the long-running popular women’s magazine. It’s been fun to compare it to the Good Housekeeping magazine from 1960 I wrote about a few weeks ago. In just that six-year span, the advertising copy grew much more florid, less concerned with keeping a perfect household and more concerned with personal sex appeal. I don’t know if it was the popularization of the birth control pill in the early 1960s that caused the subsequent cultural obsession with sexiness that sprouted in the 1960s and 1970s (as many social historians suggest), but the move from wanting a sparkling oven and a perfect meatloaf for one’s husband and children to the quest for bouncier hair, more luxurious nails and more kissable lips for an unnamed man is quite pronounced.

I love the over-the-top ad copy: “Suddenly everyone’s all eyes (and sighs!) over [Max Factor] Shadow Creme. The new glowy-eyed eye shadow that slips on like a dream, because it’s cream!” Adjectives morph into ad-copy-ready verbs to try to add youth and vigor to a phrase: with dreamy creamy eye shadow one can “sleek on a shy narrow line of color.” Or how about the nail polish which will apparently change your life with its heart-stopping, eye-catching beauty? You don’t just brush it on, you slither it on. Not slather, slither: one must apply it sexily, with the thrilling undulations of a snake. Yes, with Revlon Crystalline Nail Enamel, “Even before you slither it on, you’ll see the big difference. . . . On your nails it glows with a soft, low-key lustre. A quiet kind of chic. You’ll be smitten with the deep, velvety quality of it. The plushness. The cover. The delicate—but definite—color. Elegant beyond price.” I’m practically having palpitations just thinking of it.

Not getting enough action, you brown-haired beauties? The problem is with your makeup: you need Clairol Flicker Stick. “This is only for the brunettes who rather enjoy having their hair mussed occasionally. The very first lip gloss for Brunettes Only. Give your lips a lick of something new.” That’s wildly suggestive compared to the ads of 1960 and before. Another rather bold ad features a photo of a man in a business suit with his head and one hand both cropped away and his other hand holding a telephone. The focus of the photo is the man’s crotch, which is shown splay-legged sitting on an office chair. The headline? “If your husband doesn’t lift anything heavier than a telephone, why does he need Jockey support?”

The ad goes on to say that “During a normal day, a man makes a thousand moves that can put sudden strain on areas that require male support. Climbing stairs. Running to catch a bus. Bending. Reaching. Simple things, yet they are the very reasons why every man needs the support and protection that only Jockey brand briefs are designed to provide.” Otherwise, what, he might get a wedgie? Or lose his ability to sire a child because he ran up the stairs too fast? They seem to imply that his very manhood is in peril should he wear the wrong underpants.

The fashion emphasis by 1966 is on younger, fresher, livelier styles. The concern isn’t so much about using the latest and greatest (and shortly-thereafter-to-be-determined dangerous) drugs, pesticides and cleaning agents around the house in an effort to be more chemically controlled and germ-free, as had been so popular in 1960. By 1966 there was more of a desire to spend money and time on disposable products that made living more convenient and fun. The hedonism index rises dramatically during the 1960s, and there’s more of a desire to consume new, specialized products and live for today without concern for the cost or waste involved. There’s definitely a keeping-up-with-the-Joneses kind of jonesing for the latest, hippest disposable new thing.

For example, paper napkins and towels and coordinating tissues and became popular, and having one’s scented, dyed toilet paper match one’s scented, dyed facial tissues was a must. Ads offered bright, bold bath towels with garish flower power colors and patterns, then showed coordinating Lady Scott bathroom and facial tissue with colored flowers printed onto the paper in Bluebell Blue, Camellia Pink, Fern Green and Antique Gold. It’s a “color explosion in towels and napkins.” “Pop! go the colors of Scotkins—newly pepped-up to bring zing to table settings” and “gay bordered towels.” Don’t forget to “Scheme your tables with the vibrant new designs in the first cushioned paper placemats by Scott.” Scheme your tables?

Best of all, “Color explosion flashes into fashion with the paper dress!” For $1 plus a 25 cent handling fee you could buy a paper shift dress in a red and white bandana print or a black and white op-art geometric design. Original “Paper-Caper” dresses, still folded in their original envelopes, are now quite collectible; one of the bandana print was recently available on eBay for $25; another auction house is asking $150 for the op-art version. “Dashingly different at dances or perfectly packaged at picnics. Won’t last forever . . . who cares! Wear it for kicks—then give it the air.” Campbell’s soup cashed in on the disposable dress craze while demonstrating their pop art cred: they sold their own Andy Warhol-inspired paper “Souper Dress” printed with images of Campbell’s soup cans. Each sold for $1 plus two Campbell’s Soup labels in the sixties. Want one now? Ebay recently listed one with a starting price of $749; it sold for $1,125. Missed out on that one? Don’t worry; another has been listed for sale for $2,000.

Paper dresses were available in very simple styles, which were much like most fabric dresses of the day. Most women did at least some home sewing in an effort to economize, and almost all girls were taught to sew and cook in school, so essential were those skills deemed for females of the day. Many dresses were shapeless, boxy shifts, easy for any home sewer to whip up with a pattern bought at the nearest department store. My mother, an accomplished seamstress and knitter, never stopped with simple shifts; she made me wonderful pintucked blouses, perfectly tailored little coats, intricately cable-knitted sweaters and lovely dresses. We spent many happy hours in all the department stores’ sewing sections from as far back as I can remember. We visited the fabric departments of five-and-dimes like TG&Y (which was affectionately nicknamed “Toys, Garbage and Yardage”), popular stores like Mervyn’s and Penney’s, and slightly tonier establishments like the Bay Area’s Emporium-Capwell stores. Every good department store had a fabric section with a wide variety of materials, notions and patterns. Nowadays it’s hard to find fabric stores that aren’t superstore fabric-and-craft chains, and sewing is a niche market attended to by specialty stores only.

I don’t mean to get too personal, but do you remember spray deodorant? Wet and smelly, it got all over everything, spewed fluorocarbons into the air and ended up wasting a lot of product due to overspray, but it was oh, so popular in the sixties and seventies. But how do you market something like that to women? Like this: “Slim, trim, utterly feminine, hardly bitter than your hand . . . new cosmetic RIGHT GUARD in the compact container created just for you.” “Elegant . . . easy to hold, Right Guard is always the perfect personal deodorant because nothing touches you but the spray itself.” What a prissy little product, huh? And for those not-so-fresh moments that can’t be discussed in polite company, there was Quest, “a deodorant only for women.” It was a powder that “makes girdles easier to slip into,” among other things.

Having a separate female version of a product with prettier packaging was very popular: all sorts of spray cans and discreet boxes featured what looked like miniature wallpaper designs, floral themes and delicately drawn feminine profiles of wispy women who appeared unaware that they were being watched while they sniffed daisies (which are rather stinky flowers, actually).

I wish I could still send a quarter to Kotex for the fact-packed booklet titled “Tampons for Moderns.” One can only imagine the bouncy, well-groomed young women in the line drawings that must have illustrated the booklet, which I see in my mind’s eye as having a turquoise cover bearing a confident-looking brunette wearing a fresh white dress. (Such products are often advertised by women in white to emphasize their fresh, clean, pure quality and the idea that you won’t be the unclean mess you’ve been made to think you are if you’ll just use their products.) The booklet must have read a lot like the brochures and booklets I got at school during the seventies, full of “gee, it’s great to be a woman!” ad copy that played up the ease with which one could stay well-groomed, pretty and presentable even when afflicted by the horror of the condition that could barely be hinted at but which every female experienced. A “really, it’s not so bad!” tone lay behind every phrase and the subtle instructional nature of each conversational paragraph was supposed to allay concerns. I think it actually emphasized the unmentionable quality of the subject matter: this stuff is so important and secret, the text implied, you need official instruction books to deal with what every woman from time immemorial has gone through—but we still can’t address any of it head-on.

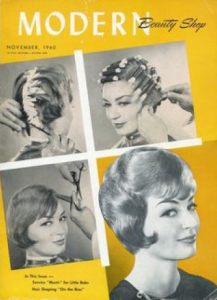

Before reading this magazine I’d forgotten just how popular hairpieces were in the sixties. They were quite common accessories and supplemented many women’s wardrobes, often with rather ridiculous results. Remember, many women still went to the hairdresser for weekly perms, blow-outs, cuts and curls and slept with their hair in hard plastic or itchy metal-and-nylon brush curlers or pincurls every night, spraying their coifs afresh with new coats of sticky Aqua Net hairspray each morning and avoiding washing their hair for as long as possible between beauty parlor visits. Adding fluffy, braided, curly, straight or poufy switches, falls or wiglets (don’t you love that word?) to the mix wasn’t a big stretch. Long hairpieces, braided or twisted, or fluffy poufs added onto the top or back of a hairdo weren’t uncommon; teasing hair up into domes, small head hillocks or B-52-large beehive cones was a regular thing. I remember women with hair that rose a good four to six inches above their heads and never moved, no matter what the weather did. Women only entered swimming pools without bathing caps in movies; public pools wouldn’t allow a woman or girl to swim unless a rubber cap, often covered in ridiculous colored rubber “petals” that came off and floated in the water, completely covered her head.

Of course, a women’s magazine couldn’t be simply about making oneself prettier for one’s man. A good housewife also had to feed him (using lots of prepared food products) and heat or chill the leftovers in appliances that came in sexy new colors and promised easy-care features. The Admiral Duplex Freezer/Refrigerator ad features eight—count ’em! eight!—exclamation points on one page, so you know it must have been a sensational product. With this fabulous appliance’s automatic ice maker, there’s “no filling, no slopping, no mess.”

But what to feed a hungry man on a hot summer night when you don’t have time to whip up a big batch of sloppy joes with Shilling’s or Lawry’s sloppy joe mix? Meat-laden salads! When housewives of the sixties grew tired of the same old coleslaw, Best Foods Mayonnaise had the answer: hollow out a cabbage, scallop the edges of the emptied cabbage head (with kitchen shears, apparently) and pack it to the brim with coleslaw into which you’ve mixed canned tuna. Or maybe you’d prefer to dollop cottage cheese, celery seeds, shredded carrots and green peppers into your coleslaw? Cottage cheese was plopped on everything in the sixties and seventies, as I remember. The iconic healthy breakfast depicted on TV shows or in ads always included a half-grapefruit with a mound of cottage cheese astride the fruit flesh and a maraschino cherry popped gaily on top. Why anyone would want to consume those three items at the same time was always a mystery to me. What if you’re not into tuna slaw or cottage cheese and cabbage? California coleslaw includes crushed pineapple and quartered marshmallows. To wow the guests at your next picnic, serve this candy-sweet coleslaw in a cabbage cut to look like an Easter basket, complete with orange peel “bow,” as shown in the ad, and you’ll “perk up wilted appetites.”

Of course, not every woman alive in the 1960s was a housewife. Many, like my single mother, worked, whether out of pleasure, necessity or both. But the jury was still out on whether those who didn’t strictly need to work to pay the basic bills had either reason or right to do so. Paying women less than men for equivalent work because it was assumed that their work wasn’t essential to their family’s income was common; refusing to promote them or extend them personal credit that wasn’t cosigned by a husband or other man was also an everyday thing. When my mom bought her own house with her own savings in 1970, it was quite an accomplishment and unusual among the people we knew.

This issue of McCall’s has a letter related to an article about working women published in a prior issue. A reader writes of having worked steadily her whole life out of necessity, but angrily derides the choices of women who work out of a desire to serve, for career fulfillment or for personal satisfaction. “I have nothing but contempt for the wives of prosperous men who, in their own boredom and greed, take jobs away from those who really need to work.” She can’t see the validity of working for personal satisfaction or from a desire to help others or to extend one’s world beyond one’s husband’s sphere. These opposing arguments played out regularly in the court of public opinion (and in courts of law) throughout the next couple of decades as women fought to be allowed the same access to education, employment and advancement without respect to whether they had as much “need” to work as men.

When the woman of 1966 worked too hard and felt depressed over her inability to get ahead on the job, whether at home or out in the world of paid employment, what could she do to find the vim and vigor she needed to get through the day when her get-up-and-go and gotten up and gone? McCall’s had the answer for that, too. Anacin, then a popular over-the-counter headache medicine (and still available at drugstores today), was touted as not just a pain reliever but a mood elevator in an ad with the headine “Casts away gloom, depression . . . as it relieves headache pain fast! Anacin has a combined new action that actually casts away gloom and depression as headache pain goes away in minutes. . . . [F]ortified with a special ‘mood-lifter’ or energizer that brightens your spirits, restores new enthusiasm and drive. With Anacin you experience remarkable all-over relief.” Wow! How did this remarkable wonder drug effect such miraculous changes? What super-effective secret ingredients were at work? Anacin’s remarkable active ingredients amounted to nothing more than aspirin and caffeine. Yes, taking two cheap aspirin and a few cups of coffee would “cast away gloom” and relieve headaches just as quickly. After all these years, now you know.