[Originally published on Laura Grey’s Little Hopping Bird blog.]

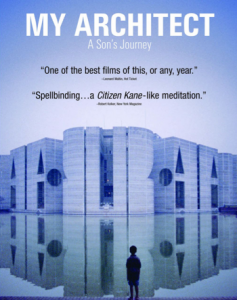

Louis I. Kahn (1901-1974) was one of the 20th century’s most influential and well-regarded architects. He designed such important structures as the Exeter Library at Philips Exeter Academy, and the Capital Complex in Dhaka (Dacca), Bangladesh, and his work was revered by high-flying architects such as I. M. Pei, Philip Johnson, and Frank Gehry. But his habits of overwork and overextension, bidding for too many projects and becoming obsessive about his all-consuming passion for architecture, led him to die of a heart attack, bankrupt and alone, in a Penn Station bathroom as he was on his way home to Philadelphia from New York. When he died, he left not only a wife and their daughter, but also a mistress and his second daughter, as well as a second mistress and his third child, his 11-year-old son, Nathaniel, who made a beautiful documentary about his father, “My Architect: A Son’s Journey.”

Nathaniel Kahn’s documentary visits and discusses the works of his father, some of which Nathaniel had never seen before, and shows the emotional and artistic impact that Louis Kahn and his work made on others, both architects and clients. But more than being a simple homage to his father and his works, the film shows Nathaniel’s search to understand his secretive, mysterious father’s compartmentalized life and to strengthen his connection to the father he lost so early. Louis Kahn’s charisma and charm, his love for his children and the feelings of great love and loyalty he engendered in the women in his life are all made clear, as are his self-absorption, his need to make every commitment in life secondary to his commitment to his work, his flashes of arrogance, and his lack of empathy for others. The question which underpins the whole film is whether the gifts of an artistic genius whose work engenders tears of appreciation from his clients and fellow architects can justify his remote, selfish, and disconnected life.

To his credit, Nathaniel Kahn doesn’t try to answer any of these questions once and for all; he interviews his two half sisters and talks with his mother, who still nurses the belief that Louis Kahn was about to leave his wife and come to live with Nathaniel and his mother before he died. He asks difficult questions and presses his mother to be honest about his father’s failings and selfishness. The responses are at times surprising and always sad and touching.

Although he admires his father’s work, Nathaniel Kahn doesn’t like every one of his father’s buildings. As he makes his pilgrimage to each one, he asks the people who live with and use the buildings how they feel about them, and admits when he finds one cold or impractical. When he visits the Exeter Library or the Institute of Public Administration at Ahmedabad, India, or when he goes to Bangladesh and sees how the Capitol and Parliament Buildings in Dhaka are enjoyed and made into the center of life for the local people, he is clearly moved. Sometimes the technical mastery of his father’s work, its appropriateness in shape, form, and function and its original and spare use of light and materials awe him, and we see him surprised and touched by the effect that his father’s work had on others.

It’s difficult to express what makes this film so watchable, moving, and fascinating. I suppose it boils down to three things I find endlessly illuminating: artistic masterworks, biographies of unusual and influential people, and bad family dynamics. This documentary is worth watching on any of those counts; as a work of art encompassing all three, it’s extraordinary.

I found a lovely site with beautiful photographs of Louis Kahn’s work; do check out “The Works of Louis I. Kahn: A Visual Archive by Naquib Hossain.” Hossain describes Kahn’s work elegantly as “A purposeful knot of complements and contradictions in a rich fabric of brick, mortar, and concrete, woven to being by natural light.” “My Architect” is a purposeful knot of complements and contradictions, too, and a lovely work of art in its own right.