The teenagers who formed U2 in 1976: Adam Clayton, Larry Mullen, Bono (then Paul Hewson), The Edge (then David Evans)

I’m rolling my eyes over the recent international Internet brouhaha over the free download of U2’s latest album “Songs of Innocence” to half a billion iPhone users. People are spewing such torrents of venomous virtual spittle in the direction of both U2 and Apple that one would think Apple had automatically deducted $100 from everyone’s iTunes account or forced a computer virus onto us all to destroy our iPhone software instead of providing millions with a musical gift created by one of the most popular musical groups on earth. I find this manufactured outrage ridiculous and feel embarrassment for the complainers. It’s like finding a magazine you didn’t order in your mailbox or a free box of cookies in your grocery bag—would you complain? Honestly, getting those free gifts would be worse—if you don’t want them, they waste resources, where as digital downloads need only be ignored or erased if they don’t strike your fancy: no calories, no wasted paper, just an intended treat that you can leave alone if it doesn’t bring you pleasure. In most cases, wouldn’t you be delighted to get a little something for nothing that you could sample and perhaps even enjoy?

The New Yorker’s Cartoon of the Day, September 16, 2014

Nobody would call this U2’s finest album, but it’s not a flaming pile of garbage, either, and critical response to the actual music is generally positive. It doesn’t have the urgency, intensity, pathos or power of their best work, but some of the songs (“The Miracle (of Joey Ramone),” “Raised by Wolves”) are catchy, pleasant enough and have some of the satisfying, pleasing style and characteristic sounds that have helped U2 sell over 150 million albums worldwide and won them 22 Grammy awards. Bono says they returned to the music of their youth for inspiration. “Songs of Innocence” is a nostalgic look back by the band toward their early years, and its title is an apt reference to a book by the great mystical Romantic poet and artist William Blake. “I found my voice through Joey Ramone,” Bono said in an interview with Rolling Stone, “because I wasn’t the obvious punk-rock singer, or even rock singer. I sang like a girl — which I’m into now, but when I was 17 or 18, I wasn’t sure. And I heard Joey Ramone, who sang like a girl, and that was my way in.”

Yet growing legions seem to be taking great delight in deriding the immensely popular band for, well, everything. But U2 has always had detractors who turned up their noses at their religious, political or social views; hate Bono’s glasses; find the band’s latest tunes derivative; mock Bono’s passionate squawks at the top of his register; find Bono’s warm baritone register pompous; make fun of the Edge’s hidden hairline; thought the band was too rebellious; think the band is too bourgeois; hate them for being too popular; hate them for not supporting the pet cause of the moment; hate them for supporting pet causes too loudly, et cetera, et cetera.

So why the anger at Apple over a surprise gift? Some complain that their privacy was invaded when Apple downloaded content to their phones. (Such silliness; you users agreed to downloads from Apple when you bought your coveted iPhones, and you each got a free present—poor you.) Others are angered because they think that giving away an album for free says somehow that music is worthless and undercuts the value of all downloaded music everywhere. But U2 was paid for their music, just directly by Apple instead of by iPhone owners. Apple and U2 certainly didn’t think the music was worthless—Tim Cook and U2 were proud and excited and felt that they were offering something of great value that would bring people joy. And people did check it out: 33 million users listened to the album in just the first six days after its release. Yet some complained that Apple chose to feature a 38-year-old band whose best years are likely behind them instead of giving a big boost to the career of a new group that hasn’t already earned over a billion dollars in sales of albums and concert tickets. (Pharrell Williams was mentioned in some quarters, but after writing and performing on “Blurred Lines,” “Get Lucky” and “Happy” among other big hits over the past 18 months, hasn’t Pharrell received plenty of attention on his own?) Apple was trying to share music by a band that already had a huge following, something that many people have shown a great interest in, a band with millions of fans who might otherwise have to shell out good money to buy their latest album, which would have sold respectably had it been sold on iTunes instead of given away. They specifically wanted to feature a really big band because it has a really big fan base, so more people would likely find it a gift of greater value. Furthermore, U2 has a long history of association with the iPod and iTunes. There was even a special U2 edition of the iPod sold in 2006. It seemed to Apple and U2 like a nice nod to their shared history. But thousands of iPhone owners are moaning as if Bono personally deleted Candy Crush Saga and all the contacts from their phones.

Most of the vituperation being shared online is aimed at the band itself, as if it had sent out boxes filled with live snakes instead of agreeing to share its music with vast numbers of listeners, something nearly every band in the world would have been happy to do if given the chance. Why be angry with a group of popular and talented musical artists for trying to widen their reach at no cost to fans or potential fans? The indignation and U2-hatred filling the ether over mass free distribution of art seems to me to be the folly of spoiled owners of luxury goods who are in a mad hurry to find something to rip apart.

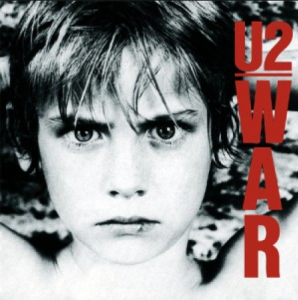

To be fair to U2’s detractors, I haven’t owned a new U2 album since I was given “The Joshua Tree” in 1987. While that album was a massive hit, garnering accolades, rave reviews and endless awards, it was never very popular with me. I didn’t dislike it, but it didn’t have the driving, intense fire I had loved in their earlier albums, and from then onward I haven’t followed them very carefully, though their radio ubiquity has meant that I was familiar with all their big hits. I’ve liked most of them well enough. But they didn’t move me like the earlier albums did. By the time U2’s members became international superstars with “The Joshua Tree,” I had been a fan for a long time, listening frequently and with great pleasure to their album “Boy” from 1980 and “War” from 1983. I loved the raw, fresh intensity of their earliest albums, which sounded like no one else’s. Bono’s voice had an urgent power, a ringing, plaintive quality that forced you to listen to it and made you want to know the story behind each lyric. Larry Mullen Jr.’s drums had the precision of a military cadence at times mixed with stunning syncopation. The Edge played with shimmering waves of reverb, his mesmerizing six-note arpeggios washing over each other as they echoed, crashing into each other like waves. Adam Clayton‘s ominous bass lines on songs like “New Year’s Day” grounded all the tenor wailing, squealing guitar and rat-a-tat snare drums that floated above it.

U2’s 1983 album “War,” which features the protest song masterpiece “Sunday Bloody Sunday”

The group channelled the Angry Young Man energy that was washing over New Wave and Punk at the time via groups like The Ramones and The Clash and singer-songwriters Elvis Costello and Joe Jackson, and they spun it in their own utterly distinctive way.

By far their greatest song to me, the one that breaks my heart, is “Sunday Bloody Sunday.” The opening track from their 1983 album “War,” “Sunday Bloody Sunday” began with a syncopated, militaristic drumbeat. To get this sound, drummer Larry Mullen did his drumwork at the base of a staircase to produce more natural reverberation in the stairwell. The driving, marching cadence was soon joined by The Edge’s strange banshee guitar howls and piercing electric violin by guest artist Steve Wickham. Then came the plaintive, questioning voice of young Paul Hewson, by then known as Bono Vox (“good voice”) and later just as Bono, asking, demanding, pleading for an end to the brutal violence and terrorist acts that were then tearing Ireland apart. The song was inspired by the sectarian and nationalist conflict based in Northern Ireland known as The Troubles. Now often referred to as the Northern Ireland Conflict, The Troubles heated up and caused enormous enmity among various British, Northern Irish and Republic of Ireland factions from the late 1960s until the Belfast “Good Friday” Agreement of 1998, and sporadic violence continued afterward despite the official end of the conflict. Terrorist bombings were all too common during this period, and the massive number of closed-circuit video cameras throughout London today are in part the legacy of British efforts to stamp out paramilitary terrorist attacks on London’s popular public gathering places by those who resented what they considered illegitimate rule by Britain over Northern Ireland. Brutality by government forces toward protesters inspired great hatred and many terrorist events and acts of resistance across ethnic, national and political lines. More than 3,600 people were killed during the conflict.

The U2 song is primarily a response to the “Bloody Sunday” incident in Derry, Northern Ireland (known to the British as Londonderry), in which British troops shot and killed unarmed civil rights protesters and bystanders who protested imprisonment without trial. The band said that the song was in response to sectarian violence in general, and they were careful to emphasize that the song was not a rebel song, took no political stance and did not advocate for either side. U2 was anxious to discourage people from hardening their attitudes based on political lines. They hoped to remind people to consider the humanity of all involved and to put treasuring human life above treasuring political philosophy. In concert, Bono has often introduced the song by waving and planting a white flag, the symbol of an end to hostilities and violence. The song became one of their signature tunes, and is among their most beloved songs and most frequently performed concert tunes. Rolling Stone rates it 272nd on their list of “The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.”

None of the tracks from “Songs of Innocence” is likely to make it onto anyone’s list of 500 greatest songs, but the album doesn’t need to be a milestone in music history to be a worthy effort. And while the members of U2 may be rich and famous and powerful enough to inspire resentment and jealousy from those less fortunate, they are still intensely competitive, creative, talented people whose hunger to perform and share their music has kept them touring and recording for nearly 40 years. They have worked hard and thrilled millions to earn their success; why denigrate them for wanting to continue to do what they love so much and have done so well? I don’t see Paul McCartney being thrown to the dogs for continuing to make albums full of pleasant but certainly not earth-shattering songs sung in a voice well past its prime; why can we not extend the same appreciation to a group of performers who are still creating lovely works that a huge percentage of the world’s population just received as free gifts and many will enjoy? Why not thank the gift horse that has provided us with beauty for all of these years instead of kicking it in the shins?