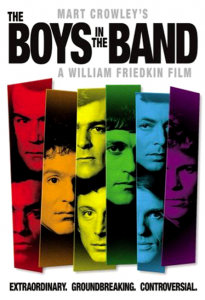

[In honor of the Broadway revival of Mart Crowley’s 50-year-old play The Boys in the Band starring Jim Parsons, Zachary Quinto, Matt Bomer and Andrew Rannells, I’m reposting this piece I wrote in 2009.]

Some years ago, while watching TV in the wee hours of the morning, I happened upon a film that I’d never before heard of. I was instantly hooked. It turned out to be a milestone in gay-themed filmmaking, a cult classic that alternately (and sometimes simultaneously) delighted and appalled New York theatrical audiences in 1968 and then moved to the screen in 1970. That film was The Boys in the Band.

Written by gay playwright Mart Crowley, the play attracted celebrities and the New York in-crowd nearly instantly after it opened at a small off-Broadway theater workshop in 1968. The cast of nine male characters worked together so successfully that the whole bunch of them made the transition to the screen in 1970, which is nearly unheard of.

Crowley had been a well-connected and respected but poor young writer when his play became a smash in 1968. While still a young man, he knew how the Hollywood game was played and how to jockey his success into control over the casting of the film. Working with producer Dominick Dunne he adapted his script into a screenplay and watched director William Friedkin, who also directed The French Connection and The Exorcist, lovingly keep the integrity of the play while opening it up and making it work on the screen.

It’s hard to believe that the play opened off-Broadway a year before the Stonewall riots that set off the modern-day gay rights movement in New York and then swept across the country. The characters in the play, and the whole play itself, are not incidentally gay—the characters’ behavior and the play’s content revolve around their homosexuality. For better or worse, the characters play out, argue over and bat around gay stereotypes: the drama queen, the ultra-effeminate “nelly” fairy, and the dimwitted cowboy hustler (a likely hommage to the cowboy gigolo Joe Buck in the 1965 novel Midnight Cowboy, which was made into a remarkable film by John Schlesinger in 1969). The play also features straight-seeming butch characters who can (and do) “pass” in the outside world, and a visitor to their world who may or may not be homosexual himself.

The action takes place at a birthday party attended only by gay men who let their hair down and camp it up with some very arch and witty dialog during the first third of the film, then the party is crashed by the married former college pal of Michael, the host. A pall settles over the festivities as Michael (played by musical theater star Kenneth Nelson) tries to hide the orientation of himself and his guests. That is, until the party crasher brings the bigotry of the straight world into the room, and Michael realizes he’s doing nobody any favors by keeping up the ruse. During the course of the evening he goes from someone who celebrates the superficial and who has spent all his time and money (and then some) on creating and maintaining a reputation and a public image, to a vindictive bully who lashes out at everyone and forces them all to scrutinize themselves with the same homophobic self-hatred he feels. He appears at first bold and unflinching in his insistence on brutal honesty, but he goes beyond honesty into verbal assault, while we see reserves of inner strength and dignity from characters we had underestimated earlier in the play. Though The Boys in the Band isn’t the masterpiece that Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? is, I see similarities between the two in the needling, bullying and name-calling that alternates with total vulnerability and unexpected tenderness.

The self-loathing, high-camp hijinks, withering bitchiness and open ogling made many audience members uncomfortable, a number of homosexuals among them. Some felt the story and the characterizations were embarrassingly over-the-top and stereotyped. They thought that having the outside straight world peek in and see these characters up close would only make them disdain homosexuals even more. This is a legitimate criticism; the nasty jibes, pointed attacks, and gay-baiting that goes on among and against gay characters here is the sort of in-fighting that could encourage bigots to become more entrenched in their prejudices when seen out of the context of a full panorama of daily life for these characters.

However, the play and film were also groundbreaking in their depictions of homosexuals as realistic, three-dimensional men with good sides and bad. Even as we watch one character try to eviscerate the others by pointing out stereotypically gay characteristics that make them appear weak and offensive to the straight world at large, there is also a great deal of sympathy and empathy shown among the characters under attack, and even towards the bully at times. Sometimes this tenderness is seen in the characters’ interactions. At other times, it is fostered in the hearts of the audience members by the playwright. Playwright Crowley has us witness people behaving badly, but we recognize over time how fear and society’s hatefulness toward them has brought them to this state.

These characters may try to hold each other up as objects of ridicule, but the strength of the dialog is that we in the audience don’t buy it; with each fresh insult, we see further into the tortured souls of those who do the insulting. We see how, as modern-day sex columnist Dan Savage put it so beautifully in an audio essay on the public radio show This American Life in 2002, it is the “sissies” who are the bravest ones among us, for they are the ones who will not hide who they are, no matter how much scorn, derision and hate they must face as a result of their refusal to back down and play society’s games. Similarly, to use another theatrical example, it is Arnold Epstein, the effeminate new recruit in the Neil Simon 1940’s-era boot-camp play Biloxi Blues, who shows the greatest spine and the strongest backbone in the barracks when he does not hide who he is, and he willingly takes whatever punishment he is given stoically and silently so as not to diminish his honesty and integrity or let down his brothers in arms.

The situation and premise of The Boys in the Band are heightened and the campy drama is elevated for the purposes of building suspense. This echoes the action in plays by Tennessee Williams and Eugene O’Neill, where the uglier side of each character is spotlighted and the flattering gauze and filters over the lenses are stripped away dramatically as characters brawl and wail. The emotional breakdowns are overblown and the bitchy catcalling is nearly constant for much of the second half of the film, which becomes tiresome. However, the play addresses major concerns of gay American males of the 1960s head-on: social acceptability, fear of attacks by angry or threatened straight men, how to balance a desire to be a part of a family with a desire to be true to one’s nature, monogamy versus promiscuity, accepting oneself and others even if they act “gayer” or “straighter” than one is comfortable with, etc.

It is startling to remember that, at the time the play was produced, just appearing to be effeminate or spending time in the company of assumed homosexuals was enough to get a person arrested, beaten, jailed or thrown into a mental institution, locked out of his home or job, even lobotomized or given electroshock therapy in hopes of a “cure.” In 1969 the uprising at the Stonewall Inn in New York City’s Greenwich Village by gay people fighting back against police oppression was a rallying cry. It gave homosexuals across the nation the strength to stand up for their rights and refuse to be beaten, threatened, intimidated, arrested or even killed just for being gay. However, anti-gay sentiment in retaliation for homosexuals coming out of the closet and forcing the heterosexual mainstream to acknowledge that there were gay people with inherent civil rights living among them also grew.

Cities like San Francisco, Miami, New York and L.A. became gay meccas that attracted thousands of young men and women, many of whom were more comfortable with their sexuality than the average closeted American homosexual and who wanted to live more openly as the people they really were. There was an air of celebration in heavily gay districts of these cities in the 1970s and early 1980s in the heady years before AIDS. It was a time when a week’s worth of antibiotics could fight off most STDs, and exploring and enjoying the sexual aspects of one’s homosexuality (because being a homosexual isn’t all about sex) didn’t amount to playing Russian Roulette with one’s immune system, as it seemed to be by the early to mid-1980s. Indeed, of the nine men in the cast of the play and the film, five of them (Kenneth Nelson, Leonard Frey, Frederick Combs, Keith Prentice and Robert La Tourneaux) died of AIDS-related causes. This was not uncommon among gay male theatrical professionals who came of age in or before the 1980s. The numbers of brilliant Broadway and Hollywood actors, singers, dancers, directors and choreographers attacked by AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s is staggering.

When the film was made in 1970, all of the actors were warned by agents and others in the industry that they were committing professional suicide by playing openly gay characters, and indeed, several were typecast and did lose work as a result of their courageous choices. Of those nine men in the cast, the one who played the most overtly effeminate, campy queen of all (and who stole the show with his remarkable and endearing performance) was Cliff Gorman. He was a married heterosexual who later won a Tony playing comedian Lenny Bruce in the play “Lenny,” which went on to star Dustin Hoffman in the film version. Gorman was regularly accosted and accused of being a closeted gay man on the streets of New York by both straight and gay people, so believable and memorable was his performance in The Boys in the Band.

The play is very much an ensemble piece; some actors have smaller and more thankless roles with less scenery chewing, but it is clear that it was considered a collaborative effort by the cast and director. The enormous mutual respect and comfort of the characters with each other enriched their performances and made the story resonate more with audiences than it would have otherwise. The actors saw the film and play as defining moments in their lives when they took a stand and came out (whether gay or straight) as being willing to associate themselves with gay issues by performing in such a celebrated (and among some, notorious) work of art. When one of the other actors in the play, Robert La Tourneaux, who played the cowboy gigolo, became ill with AIDS, Cliff Gorman and his wife took La Tourneaux in and looked after him in his last days.

In featurettes about the making of the play and the film on the newly released DVD of the movie, affection and camaraderie among cast members are evident, as is a great respect for them by director William Friedkin. Those still alive to talk about it regard the show and the ensemble with great love. As Vito Russo noted in The Celluloid Closet, a fascinating documentary on gays in Hollywood which is sometimes available for streaming on Netflix, The Boys in the Band offered “the best and most potent argument for gay liberation ever offered in a popular art form.”

According to Wikipedia, “Critical reaction was, for the most part, cautiously favorable. Variety said it ‘drags’ but thought it had ‘perverse interest.’ Time described it as a ‘humane, moving picture.’ The Los Angeles Times praised it as ‘unquestionably a milestone,’ but ironically refused to run its ads. Among the major critics, Pauline Kael, who disliked Friedkin and panned everything he made, was alone in finding absolutely nothing redeeming about it. She also never hesitated to use the word ‘fag’ in her writings about the film and its characters.”

Wikipedia goes on to say, “Vincent Canby of the New York Times observed, ‘There is something basically unpleasant . . . about a play that seems to have been created in an inspiration of love-hate and that finally does nothing more than exploit its (I assume) sincerely conceived stereotypes.'”

“In a San Francisco Chronicle review of a 1999 revival of the film, Edward Guthmann recalled, ‘By the time Boys was released in 1970 . . . it had already earned among gays the stain of Uncle Tomism.’ He called it ‘a genuine period piece but one that still has the power to sting. In one sense it’s aged surprisingly little — the language and physical gestures of camp are largely the same — but in the attitudes of its characters, and their self-lacerating vision of themselves, it belongs to another time. And that’s a good thing.'” Indeed it is.

[Originally published in June 2009.]